According to Anderson, Lukács was against intuitionism, but his arguments are weakened by the outright rejection of any romanticism in The Young Hegel (139). Lukács was one of the first Marxists of his times who argued about the centrality of the “standpoint of the proletariat” 5 and the criticality of the idea with reference to how he views the totality being in a dialectical relationship with the existing capitalist reality (132). 4 Anderson argues that Lukács attempted to recover the revolutionary dialectics of Hegelian Marxism from crude materialist writings that had dominated much of the revolutionary praxis of the twentieth century (126). The book also references the Hungarian philosopher György Lukács and his often-neglected work The Young Hegel. There is a considerable amount of discussion on Lenin’s Philosophical Notebooks, which have been relatively undiscussed in other books and writings on the questions of dialectics. But, with Marx, this notion of contradiction finds a materially tangible basis within the realm of political economy.Īfter discussing Hegel and his relationship with Marx’s writings, the book moves further on to the Russian revolutionary Vladimir I. For example, in Hegel’s writings, elements like contradiction are usually presented within the realm of human consciousness, which though “rooted in the experience of human labor, is privileged over the fullness of human praxis, both mental and manual” (15). 3 Marx critiqued the conservative aspect of Hegelian socio-political theory and emphasized the ideas of Hegel that bring forward the centrality of the dialectical mode of thinking. However, with Hegel, as with other thinkers like Darwin, there are two schools of interpretation-one on the right and one on the left.

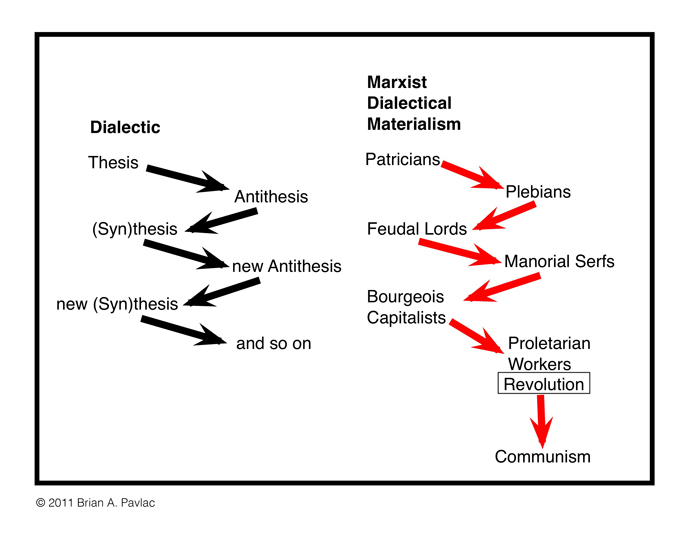

These two epochal events form the backdrop for most of Hegel’s influential works. The book begins with his and Peter Hudis’s 2 jointly written piece on the concept of dialectics, in which they argue that Hegelian dialectics is embedded within the socio-historical development of human civilization, especially focused on the periods ranging from the Age of Enlightenment to the French Revolution in 1789 (13). However, because of the broad stretch of time that these essays cover, there are certainly some discontinuities (5), but they only add to the original scope of the book because they add to the human development of the particular intellectual, especially one with as diverse a field of operation as Kevin Anderson. His academic writings have focused on the primacy of dialectics not only as a mode of analysis but a philosophy of organization and Marxist working-class movement itself (4). The most interesting part of his critiques and appreciations of thinkers is that throughout the course of the book, Anderson never really criticizes merely for the sake of critiquing but instead keeps referring the reader back to his primary agenda, which forms the vantage point through which he is looking at the ideas- Dialectics.Īnderson has been a committed Marxist-humanist for the last four decades. He also takes up positions regarding prominent social thinkers of the contemporary era, which include Pierre Bourdieu, Giles Deleuze, and Antonio Negri among others. Beginning from Hegel, Anderson extends the discussion to Marx and then further on to Marcuse and Lukács. Anderson’s 1 latest offering, Dialectics of Revolution, brings forward diverse perspectives on the concept of dialectics that have been discussed over the past two centuries.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)